In an interesting development, the design of the well-known wooden rowing machine, the WaterRower, is not protected by copyright, according to a recent judgment of the UK High Court. Can functional items be protected in the UK post-Brexit? Read our Intellectual Property team’s analysis of the case.

The Intellectual Property Enterprise Court (IPEC) in the UK has recently delivered its long-awaited judgment in the WaterRower case. The Court held that the WaterRower wooden rowing machine is not protected by copyright because it does not meet the requirements of a ‘work of artistic craftsmanship.’ This decision is at odds with EU case law like Cofemel and the Brompton Bicycle. In Brompton Bicycle, it was held that the only requirement for an identifiable object to qualify for copyright protection is originality. Significantly, the IPEC judgment went so far as to state that UK and EU law in this area is incompatible. We consider the decision and its implications for designers.

Background

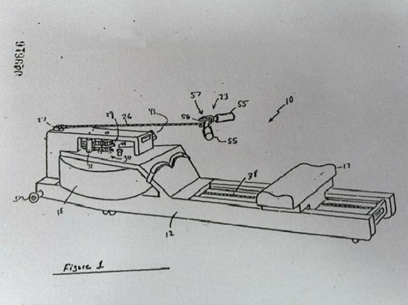

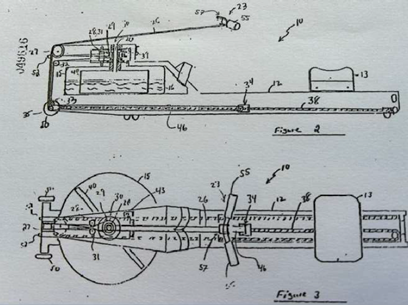

The original WaterRower was designed by a former rower named John Duke. Mr Duke’s evidence was that “the Prototype”, the first copyright work, was reproduced in 2-D drawings in a US patent application. This application was filed in May 1987.

Mr Duke explained he intended to create a “clean design…with lots of plain edges without fancy ornamentation…in the structure it follows the ‘form follows function’ school of design.” The shape of the frame was also consciously designed bearing in mind the loading forces required to “drive” the rower. He further noted that the flywheel tank needed to be round, but the cross section was made largely rectangular, “to reprise the rectangular cross section of the wood parts” and the seat was “stitched as you would find in the seats of a fine sports car.”

The key question which arose in the case was whether Mr Duke’s design of the WaterRower is protected by copyright in the UK as a work of artistic craftsmanship.

IPEC decision

Originality

The Court held that the Prototype is technically restricted in certain aspects of its design to allow for the rowing machine to function mechanically. That being said, Mr Duke made choices in the:

- Layout of the Upper Deck and Lower Deck

- Width of the Main Rails, the wood used

- Shape and finish of the wood

- Carefully thought through relationships of the angles, spacings and joins relating the various component parts of the shape, including the Upper and Lower Decks to create a “repeating motif of parallel structural elements in different planes and scales”

There was therefore room for Mr Duke to reflect his personality in the design. The Court was satisfied that the Prototype is original in that the design is Mr Duke’s own intellectual creation as a work under copyright law.

Artistic craftsmanship

Evidence including newspaper articles and commercial journals were furnished showing that a significant section of the public found the WaterRower design aesthetically pleasing. The Court also noted that the presence of the WaterRower models in commercial design stores, including MOMA, indicated high regard for the quality of the design.

However, in the Court’s view, these useful contemporaneous documents do not give the impression that the design was the result of a mind with a desire “to produce something of beauty which would have an artistic justification for its own existence,” or “was an artist in that he used their creative ability to produce something which has aesthetic appeal.”

Instead, the WaterRower was a commercial development, chosen from a number of rowing machine ideas. It was chosen as the design most likely to achieve Mr Duke’s business goal: creating a commercially successful rowing machine with a design of aspirational sensory impact. Ultimately, and for this reason, the Court concluded that the Prototype is not a work of artistic craftsmanship and is therefore not capable of copyright protection as a matter of UK law.

Comment

The case is interesting not only in illustrating the difference between copyright protection for functional items under UK and EU law, but it also demonstrates the interplay between design rights and copyright. If the EU approach had been followed for example, this would potentially allow a wide range of functional items to benefit from copyright protection as opposed to design protection, which is much shorter in duration. Similarly, the outcome of the decision means that a design could be protected by copyright in the EU, but not in the UK. This outcome is clearly unfavourable for creators of designs which are both functional and creative. This decision is also likely to cause confusion in the UK design community going forward.

The approach of the IPEC is also interesting in that the decision followed the UK Supreme Court judgment in Lucasfilm Ltd v Ainsworth[1]. This case related to Stormtrooper helmets and armour. The Court held that while the production of the items by Mr Ainsworth was an act of craftsmanship, the items themselves were not works of artistic craftsmanship. Post-Brexit however, the CJEU authorities have clearly been departed from in the UK. This was because, in the view of the IPEC, the originality requirements that align copyright protection with sections 1 and 4 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (as amended) do not extend to requiring artistry in craftsmanship. Extending them in this way “would go against the grain” of the legislation’s wording and “distort the intention of Parliament.” Section 4(1)(c) of the Act was specifically excluded from this consideration.

Against this backdrop, clarity on the legal standard for copyright protection for functional items in the UK would be welcomed. This case could be resolved by a superior Court in the UK. i.e. the Court of Appeal or the Supreme Court, if the IPEC decision is appealed. Alternatively, the UK legislature could also decide to intervene in the interim.

For more information on successful copyright protection, contact a member of our Intellectual Property team.

People also ask

Is copyright registrable? |

Not in Ireland, the EU or the UK. It subsists automatically on creation. |

Does copyright protection last longer than design protection? |

Yes. Generally, copyright lasts for 70 years after the death of the author/creator, depending on the type of work. Registered designs grant protection for 25 years. |

Could this decision be appealed? |

Yes. Generally, copyright lasts for 70 years after the death of the author/creator, depending on the type of work. Registered designs grant protection for 25 years. |

The content of this article is provided for information purposes only and does not constitute legal or other advice.

[1] [2008] ECDR 17,

Share this: