The recent spate of sanctions applied against Russian entities and persons has led to a high degree of uncertainty around some debt capital markets transactions. Market participants may encounter issues with:

- The ability of certain issuers to make repayments

- Whether paying agents can or will process such payments, and

- Concerns around investors/noteholders retaining some payments that they receive, etc.

In this context, it is worth re-examining the fundamental issue of what an investor actually owns when it acquires notes in modern debt capital markets transactions. Given how these transactions are now structured, what an investor thinks it is acquiring may be very different to the legal reality.

Background

Traditionally, debt securities in debt capital markets transactions were issued in physical form, typically referred to as definitive notes or certificates. These were held directly by the investors. This meant that when an investor invested in a bond or note issuance, it received a physical paper document which represented the bonds/notes it had purchased. When this was the case, the investor’s ownership of, and title to, the bond/note was either established by actual possession of the physical bond/note (bearer form) or by entry of its name into a register of bond/note holders (registered form). Whichever the case, under this traditional direct physical/paper method, legal title/ownership of the debt securities tended to be reasonably straightforward.

While the legal concepts associated with physical/direct ownership, in bearer and registered form, continue to have legal and practical relevance, a world where investors are typically issued with, and hold, physical certificates is no longer the norm. A big driver for this development was the logistical and custodial complexities of issuing physical securities and managing payments in respect of physical securities. This was particularly true where investors may be located in multiple jurisdictions. Now, due to the advent of “global” notes, where one physical note/bond is issued to represent an entire issuance, direct/physical methods of holding securities have now been replaced, almost universally, with indirect holding structures or “intermediated” securities.

In this scenario, a third-party custodian will typically hold the securities on behalf of the investor. The investor only has an interest in the securities through a chain of intermediaries that have been placed between it and the issuer. There is now a clear split in ownership: the third-party custodian is the legal owner, and the investor is the ultimate beneficial owner.

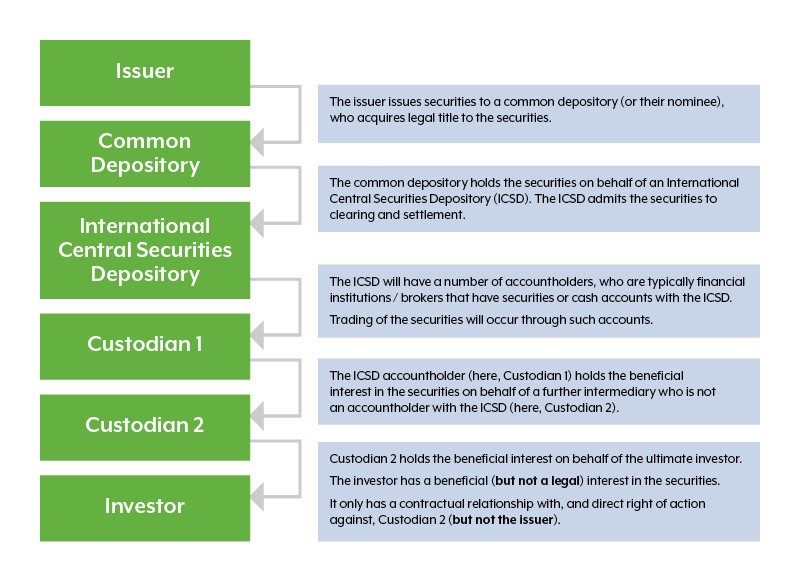

Indirect holding structures are also known as “no look through” structures, meaning that the investor can interact with its immediate intermediary only. It cannot interact with any other sub-custodian or intermediary ‘up the chain’, nor can it interact with the issuer. An example of a structure for intermediated securities would be:

It is worth noting that moving to the intermediated securities model has led to a number of benefits for capital markets generally, including:

- Greater transaction efficiency

- Smaller risk of loss or theft of negotiable instruments, and

- Cheaper, quicker and more convenient trading

Disadvantages for investors

Despite the benefits, intermediated securities undoubtedly put the investor in a different legal position than if they held their securities directly. They no longer hold the direct legal interest in the securities and instead acquire the ultimate economic interest. [1] They have been described as having “an equitable interest in another equitable interest of another equitable interest of a legal interest”. [2]

Additionally, the investor is only connected to the issuer indirectly via the intermediaries in the structure. For an investor to enforce its rights against the issuer, it must in theory work its way ‘up the chain’ through each of the contractual links that one intermediary has with another. Contracts between intermediaries will set out, for example, how and when notices, dividends, voting rights, etc. are passed up and down the chain to the ultimate investor. They will also contain restrictions on what the intermediary is obliged to do. [3] This means that the rights of the investor as set out in the issue documentation are, in reality, restricted to the least favourable contractual term in the contractual chain between it and the issuer – the “lowest common denominator” term.

Debt securities and the role of a trustee

The presence of a trustee can offer comfort to investors dealing with intermediated debt securities. A trustee acts on behalf of the investors (noteholders) and represents their interests throughout the life of the debt securities (notes). Trustees are typically experienced professional trust corporations and will be appointed pursuant to a trust deed entered into between the issuer and the trustee. They will hold the trust property, such as covenants of the issuer and any money received by the trustee relating to the notes, and any transaction security, on trust for the noteholders.

In the event of certain breaches of the issue documentation, noteholders have comfort that the trustee will act on their behalf to protect their rights. The trustee may, for example, pursue early redemption of the notes or enforce security, if any. As the trustee has a direct contractual link with the issuer (pursuant to the trust deed), some of the problems noteholders might encounter if acting individually will not be relevant (such as establishing a right to claim against the issuer or working ‘up the chain’ of intermediaries to reach the issuer).

Noteholders will usually have a right to convene noteholder meetings and vote on certain matters, such as changing the terms of the issue documentation or directing the trustee to take action including enforcing security. Typically, the trustee must convene a noteholder’s meeting if requested to do so by holders of at least 10% of the aggregate principal amount of the Notes then outstanding. This is a relatively low bar and means that even ‘minority’ noteholder(s) can have their voice heard by convening noteholder meetings.

Conclusion and next steps

Intermediated securities have altered the legal rights of investors in securities and, in certain scenarios, have made it more difficult for investors to enforce their rights. This has led some commentators to state that, “when things go wrong, the ‘no-look through’ approach will often leave the ultimate investor with no effective remedy”. [4]

This conclusion arguably does not take account of the important protections a trustee can offer investors in debt capital markets transactions. The trustee can play a crucial role “when things go wrong” and, more generally, represents the interests of the investors during the lifetime of the securities.

With many investors in capital markets transactions facing uncertainty as a result of recent sanctions, this serves as a further reminder for trustees and their legal counsel of the importance of ensuring that issue documentation contain robust trustee provisions and noteholder protections.

For more information, contact a member of our Debt Capital Markets & Listing team.

The content of this article is provided for information purposes only and does not constitute legal or other advice.

[1] Eckerle v Wickeder Westfalenstahl GmbH [2013] EWHC 68 (Ch) [2014] Ch. 196

[2] Micheler, Eva (2015). Custody chains and asset values: why crypto-securities are worth contemplating. The Cambridge Law Journal, 74(3), 505-533.

[3] See for example the standard terms of Clearstream Banking, S.A. which states, in Article 15 that it: “… has no obligation to take any action with respect to any rights, options or warrants, nor to attend on behalf of or represent the Customer at meetings of holders of Securities nor at any other occasion where action by the holder of Securities is required or permitted, except to the extent that CBL has been explicitly instructed by the Customer, and has, in writing, agreed to take such action or as otherwise provided in the Governing Documents.”

[4] Salter, Richard (2016). Intermediated securities and the rights of the ultimate investor. Journal of International Banking and Financial Law (2016) 3 JIBFL 153.

Share this: